When I was thinking about writing this thread, I originally thought it might be only 10 or so posts long, and I could put it on my Twitter. I could not. To treat the subject properly, I needed to put it in a long form.

If you’ve been linked here from there, welcome to the rabbit hole of Neoclassicism, crusading Christians, imperialism, racism, and Nazi ideology that is the reason why Greek myths are almost exclusively told and retold by white, middle-class people from England.

A few days ago, Tordotcom announced a new anthology of diverse Greek myths, retold by diverse authors. Nothing wrong with that, right? Greek people are pretty diverse—I mean, Greek people can be queer, trans, non-binary, and our diaspora is one of the largest and most widely spread in the world. Greeks are brown and black and every color besides.

Oh, what’s that?

Oh.

Ok.

Not a single Greek author on the list.

Oh, but maybe they—ok, they applied, and were rejected, on grounds we are left to assume mean that the stories and their authors weren’t diverse enough.

Of course, this is no surprise to Greek people. We know what’s going on here. But you might not know, and that’s why I’m writing this.

So, you might ask, what’s the big deal about yet another Greek myth retelling that excludes Greek people?

Well, like any great story, it spans more than 5000 years of history, has a guy named Ovid, involves several empires, multiple eugenicists, and the Nazis.

Publius Ovidius Naso, or Ovid as he’s known in English, was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus, and is one of the most influential poets (hell, artists) of all time. Truly the Beyonce of Ancient Rome.

While an erotic fiction writer1, he worked on his opus, Metamorphoses (hey, we all gotta pay the bills somehow). It was a hugely transformative work, integrating Greek and Roman myths from the creation of the universe, to the foundation and sacking of Troy, to the godhood of Julius Caesar2.

"It may be doubted whether any poem has had so great an influence on the literature and art of Western civilization as the Metamorphoses" says Melville in his translation. Romeo and Juliet is based on Ovid's story of Pyramus and Thisbe. Most of Prospero's speech in The Tempest is taken verbatim from a speech by Medea in Book VII of Metamorphoses. The Canterbury Tales was hugely influenced by several of Ovid's myths.

But why? How did it end up so influential in the first place? Well, strap in and find out. You’re in for a bumpy ride. If you look to the right, you might see some neo-nazis.

You might be surprised to know, considering how influential it was, that nothing remains of the original manuscript of Metamorphoses today. But we do know it was copied down by contemporaries and copied and recopied over a thousand years. It became hugely popular in Late Antiquity and into the Middle Ages, where it persisted in popular consciousness despite Church attempts to stamp it out. But wait—I’ve just elided about 500 years with a couple of sentences. Who copied down the original and how did it spread?

Enterprising Greeks and Romans who wanted to make a buck, probably (or a solidii, but the point stands). So why is this important?

It’s not, really. Except Ovid invented some myths whole cloth (like the story of Pyrasmus and Thisbe), and others he metamorphosed (get it… no, ok, I’ll stop).

Changing the source material wasn’t out of the ordinary for Classical Roman and Greek poets. Nicander of Colophon (one of Ovid’s influences) changed much of the material he drew from. This was a tradition spanning all the way back to Homer and likely beyond, who is thought to be a collection of poets, while the Iliad and the Odyssey are likely epic poems collected and retold in a complete package. We have been telling and retelling stories since we sat around fires and told that first story on the plains of Southeast Africa.

What made Ovid’s transformations so pernicious was their popularity.

When the West of the Roman Empire fell to the Goths in 476, the East turned its eye eastward to trading/fighting/trading and fighting some more with the Persians, and laying claim to the riches of Central Asia. They dealt with migrations and incursions3 and the rising Arab Caliphate in the south. That left them mostly uninterested and incapable of expending a huge amount of effort and manpower to reclaim the West. The East had become Hellenized, too: Greek was the lingua franca, and Constantinople was at the center of Europe and Asia. Rome had become a Germanic- and Latin-speaking backwater. Why reclaim it?

That isn’t to say they didn’t try. In the 500s, Emperor Justinian I and his tactically gifted general, Belisarius, reclaimed large swathes of Italy. Ravenna, Sicily, Naples, and many other regions fell under the four Betas. At the same time, the Latin West didn’t really fall either: it continued under the Gothic kings as a client state of the East for another few hundred years, until the Lombards invaded Northern Italy. This event would define the coming millennia.

Already the Western Christian Church (those in Rome) and the Eastern Church (those Constantinople) had grown apart (I promise I’m going somewhere with this). The East considered the West as Germanic barbarians, and the West considered the East as effeminate and pompous. It was only a matter of time before the two churches became separate entities.4

The death knell of a unified West and East church sounded when Irene of Athens sat the throne. Originally regent for her son, she locked him up and claimed the throne as Basileus5, effectively making her Emperor (yes) of the Romans. The old Roman laws said that only a man could sit on the throne, so she sat on the throne as a man.

This pesky law would prove to be the end of cordial West and East relations for more than 1000 years. In 800, a pope who was becoming increasingly infuriated with his obstinate eastern counterparts, saw the throne of the Romans as vacant, since a woman could not sit there. He crowned Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans, founding the Holy Roman Empire6.

This, as you can imagine, pissed off the East.

Another couple centuries of religious infighting and distancing of the Latin West and the Greek East, and in 1053, Pope Leo IX denied the Patriarch of Constantinople his title7 . In response, the Patriarch excommunicated Leo. The Eastern Church and the Western Church formally separated, though they had mostly already gone all the way, anyway. It’s also important to note that for hundreds of years by this point, the East spoke Greek and were culturally Greek, while the West spoke a bunch of different languages (Germanic languages, and were mostly culturally Frankish) and the Western clergy spoke Latin.

"What the fuck’s Ovid's stories got to do with this? You've just skimmed about six hundred years of history."

Well, my friend, here is where it gets bloody.

This is where the crusades begin.

Up until then, Jerusalem under the Persians and later the Arabs had flourished. Many Christians undertook pilgrimage, lived, prayed, and died there without trouble for centuries (though they had to pay the Jizya, the tax on non-Muslims). Then, the Seljuk Turks seized the city, and suppressed the infidel, forcibly converting them. In response to a popular revolt, the Turks killed many in a bloodbath. The East could do little about it, dealing with Seljuk incursions of their own. Emperor Alexios I asked for help from Pope Urban II in reclaiming Jerusalem.

Urban's response went far, far beyond anything Alexios imagined.

In 1095, Europeans looked to the skies and saw a meteor shower, a comet, and a lunar eclipse. What could these portents mean? To Urban, it was a sign of the end times, and he traveled to Claremont to deliver a speech of such lurid and epic details that it would make Trump blush. He spoke of pilgrims being slain by Turks and their heads paraded on the walls of Jerusalem. Urban declaimed a new kind of pilgrimage in response: an armed pilgrimage.

A mighty host formed, and a Crusade was called.

The First Crusade was incredibly successful. The Franks seized Jerusalem in 1099 and founded the Crusader Kingdoms, much to the chagrin of Alexios, who wanted Jerusalem for the Romans. But feelings on the matter weren’t to last long since, as you can imagine, the Crusader Kingdoms didn't last surrounded by a Muslim enemy set on revenge.

When the Outremer kingdoms fell, the Second Crusade was called. The Crusades would prove to be grisly, dismal things, including the Venetian Crusade, and the Albigensian Crusade. Far from being pious, righteous wars against a murderous infidel (although the Turks saw the Franks that way, too, for good reason), the Crusades were grisly, greedy affairs that butchered many nominally Christian people (and people of all kinds) and seized far more wealth than religious piety.

Meanwhile, the political and religious landscape of Europe was shifting. With the English invasion of France and the German pushback against the Papal States, continued fiascos in the Levant soured opinions on more crusades. The Third Crusade wasn’t a defeat as such, but it failed to capture Jerusalem, the stated aim. The appetite for crusades among the kings of Europe had turned.

Then we get to the Fourth Crusade. That noise you just heard was every single Greek and Near East historian sighing in collective sorrow. The Fourth Crusade’s stated aims were like the rest: reclaim Jerusalem for Christians.

They would do anything but.

Enrico Dandolo, the blind Doge of Venice, was 85 when he was elected in 1192. Trade had made Venice rich and confident, its formidable navy defending its wealth. That Venetian Crusade mentioned earlier forced Constantinople to make trade concessions that made them the dominant power in the Mediterranean.

Aristocrats in Constantinople disdained the Venetian upstarts as parvenus and mountebanks; newly rich, boorish sailors and shopkeepers. The Venetians, in turn, saw the Romans as effete snobs living off the fading prestige of their once-glorious name.

In 1199, Pope Innocent III (whose name is fiercely ironic considering the atrocities he incited—the aforementioned Albigensian Crusade among them) called for another crusade to reclaim Jerusalem. French nobles and their soldiers answered him. Their leader, Boniface of Montferrat, sent envoys to Venice to ask for ships to aid them in their crusade. They were to follow Richard the Lionheart’s recommendation to enter the Levant through Egypt, but they needed Venetian ships to carry their promised 33,000 soldiers and horses.

Dandolo agreed to transport 4,500 soldiers and horses through the Mediterranean to attack Egypt in 1201. But it was all a ruse. Venice had signed a trade contract only months prior with Egypt, stipulating that they would not invade Egyptian territory. The French were unaware of the contract, it seemed, and this would only be the start of their bungles.

Through a combination of ineptitude, impoverishment, and Venetian manipulation, they set their sights on a vulnerable Constantinople, which had been weakened by infighting and wholesale liquidation of their military by a succession of bad emperors. Philip of Swabia, the brother-in-law of one of the pretenders to the throne, Alexios Aggelos, wrote to the Crusaders and promised them riches and glory if they helped Alexios claim the throne. He said that Alexios promised them 200,000 silver marks, riches beyond their wildest dreams.

Constantinople was taken by the Crusaders, and Alexios placed his father Isaac (who had been usurped only years earlier) on the throne. This put the Crusaders in an awkward spot: Isaac had never promised the Crusaders the 200,000 marks, but he agreed to give them what they wanted. However, the usurper who had taken the throne from Isaac escaped with most of the treasury, and Isaac was forced to melt down the frames of valuable idols to extract their gold and silver to pay the Crusaders. Even so, he could only raise 100,000 silver marks, half of which went to the Venetians, who had an agreement with the Crusaders that they had claim to half of any booty.

The Crusaders were still in huge debt to the Venetians, while the implacable Dandolo threatened to strand them in Constantinople unless he got what he was owed.

Resentment among the people of Constantinople festered for the reinstated emperor and the strident Crusaders. Skirmishes between disgruntled Roman soldiers and Crusaders broke out. Over two years rancor built. Eventually, the Doge and the Crusaders met with Emperor Alexios IV (Isaac’s son), who said he had no intention of giving them more than he already had.

When Alexios returned to his palace, a hirsute counselor, Mourtzouphlos (bushy-brow), entered his room the next night and strangled him, seizing the throne for himself. Now crowned Alexios V, Mourtzouphlos cut off the Crusaders’ gold and food supply, hoping they would be strangled themselves and finally leave.

But his move had the opposite effect. The murder of the young Alexios IV outraged the Crusaders, who said that the faithless act meant the Romans forfeited all rights to their lands. The faithless heretics of the East were to be made obedient to the Western pope, by force. They denounced the Romans as “the enemies of God”.

Two years of boiling frustration, greed, and rage erupted on the terrified people of Constantinople. Unarmed men were put to the sword. They dragged away women, raped nuns in their convents. Icons and books burned. Statues from antiquity were melted down for their bronze or destroyed. Everything of value was taken and anything that couldn’t be carried was put to the torch (as was the custom). The Venetians, who had a better understanding of the true value of the works of art around them, carefully crated up what they found and sent them home.

After three days of looting, the Crusaders divided up the brutalized Romans into various Crusader states, and formed the Latin Empire. On May 16, 1204, Baldwin of Flanders was made the first Latin Emperor of Constantinople, and in his hands was placed a ruby the size of an apple.

It was only to last 57 years, but their successors, the Greek Palaeologoi, would inherit a depleted, plundered empire, where weeds grew waist-high in the great forums of Constantinople. The Palaeologoi revived the empire for a time, but it was like keeping someone on life support. The damage was done. More and more Imperial territory fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks, and only 250 years later, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, and began 368 years of Turkish colonization and oppression.

Venice emerged as the true beneficiary of the Fourth Crusade. Greek and Roman antiquities and valuables entered Europe through their hands, and were sold to the highest bidders (though of course, the Venetians kept some of the best prizes for themselves). In the fall of one empire, the founding of another, and events that would lead to the foundation of yet another, Europe experienced an immense cultural rebirth (I think you see where I’m going).

The Renaissance was a direct result of the Fourth Crusade.8

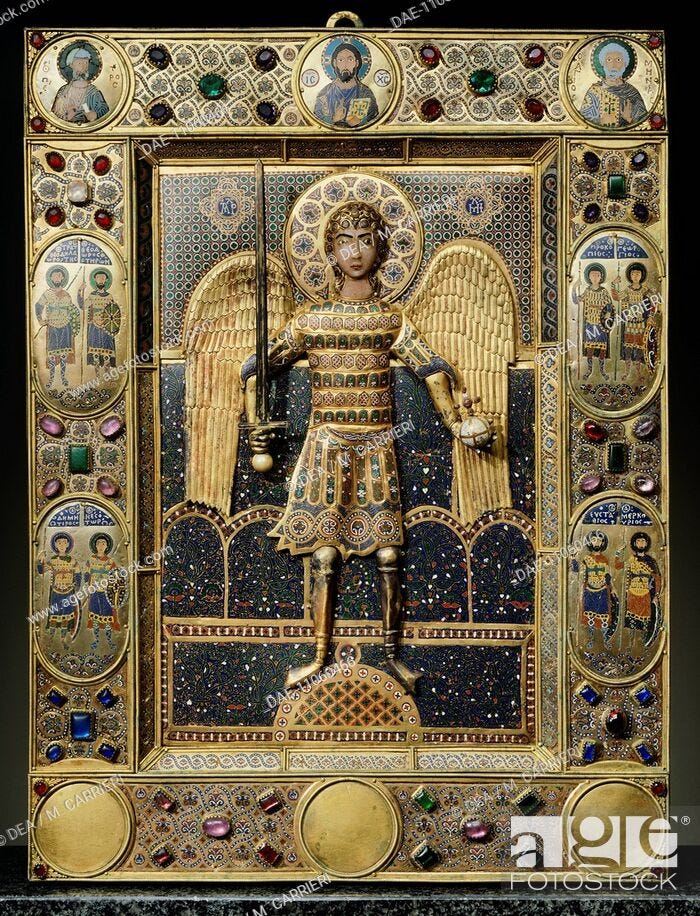

European art flourished, and Hellenistic myth became a prime subject for many artists. Hellenism became fashionable, and it is here that Ovid’s stories would emerge as among the dominant versions of myths for hundreds of years. Dante Alighieri would base his works on Ovid’s conceptions of Hades and more. The Cherubim, prior to the Renaissance, was portrayed as a multiple winged creature with the heads of an ox, a lion, an eagle, and a human. After 1420, they appear as the little boy you see in the popular conception, being Amor (Cupid) more-or-less directly from Ovid.

The popularity of Ovid’s myths surged through a different Europe, one dominated by the English, the French, the German. Here is where Geoffrey Chaucer and Shakespeare and many, many others were influenced. With the invention of the printing press in the mid-1400s, translations of Ovid’s works were everywhere, and an increasingly literate aristocracy read and shared myths that vibed Hellenistic (despite being made up by a Roman whole-cloth or changed drastically). Biases in translations crept in, and the meaning of much of the original text was lost. Not everyone could learn the original Greek, so the public conception of these myths came from inaccurate or downright harmful translations.

Other forms of art had their own biases, or their own ignorances. By the time of the Renaissance, statues (that were always painted in antiquity) had faded, chipped, or been wiped clean of their paint because the owners thought the fragments were dirt. Da Vinci and Michaelangelo had no idea that the figures had been painted, because the paint had disappeared by their day.

Styles and fashions in Europe by the 1700s had moved away from ancient ideals for the most part, until they received manna from heaven when Pompeii and Herculaneum were rediscovered. It started a revolution, and a generation of European art students toured Italy and returned home with Greco-Roman ideals. Though, what they returned home with was new, white-washed versions of them. The father of art history and Neoclassicism, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, wrote of white marble sculptures as depicting the “epitome of beauty because the whiter the body is, the more beautiful it is”. Color in sculpture came to mean something lesser, something non-white, for they assumed that the lofty Ancient Greeks were too sophisticated to color their art.

The Age of Enlightenment had begun, and with it, neoclassicism. Neoclassical writers, talkers, patrons, and artists all paid homage to an idealized Ancient Greece, though what they mostly embraced were Roman and later Renaissance copies of Hellenistic works. They ignored both Archaic Greek art and the works of Late Antiquity. As Greece at the time was inaccessible, a “rough backwater” of the Ottoman Empire, dangerous to explore, how could the Neoclassicists claim their art heritage to Ancient Greece? What were they drawing inspiration from? Well, Winckelmann’s comments on Roman ruins in Italy, the surviving copies at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and the smoothed, corrected, “restored” iterations of Greek art, developed from those stolen by the Venetians all those years ago.

For most, the movement wasn’t intentionally ignoring real Greek stories and folklore. In fact, the Philhellenes in the late 1700s—those like Lord Byron and Victor Hugo—were well-liked in Greece, and many Greeks liked them, because they advocated, rightly, for Greek independence. There’s just no reason to believe that the original folklore were the stories that spread9. There’s a huge disconnect between the Neoclassical movement—filtered through the Renaissance and several hundred years of shifting interpretations—and the actual Ancient Greece.

For some, the truth was inconvenient. Johann Schliemann was an archeologist credited with the rediscovery of the ancient site of Troy, which is in modern-day Turkey. Schliemann began digging at the site at Hisarlik in 1870, and by 1873, he had discovered nine buried cities, but none at the level that they should have been to be the ancient site of Troy. He found pure copper and metal molds as well as tools, cutlery, shields, and vases. His methods were brutal, and he had no formal education in archaeology, says C. Brian Rose:

“…dug an enormous trench, which we still call the Schliemann Trench. …He destroyed a phenomenal amount of material.”

In his blundering and obsession with finding the ancient site of Troy, many irreplaceable artifacts were destroyed. Of what was found, it’s hard to determine provenance. He kept no actual records, no mapping of finds, and very few descriptions of discoveries.

Imagine if he’d just asked one of the locals; one of the Anatolian Greeks, or the Rum, Greeks who still live in Istanbul and have lived there for millennia (being the survivors of the Sack of Constantinople in 1453).

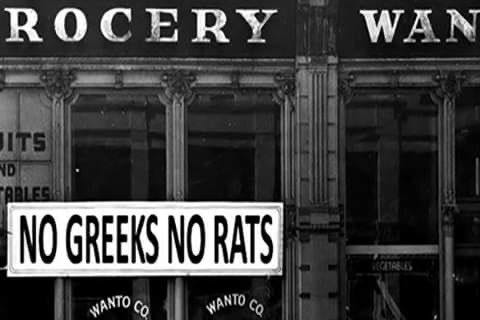

Views like those of Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer (1790-1861) were not uncommon: “The race of the Hellenes has been wiped out in Europe. Physical beauty, intellectual brilliance, innate harmony and simplicity, art, competition, city, village, the splendour of column and temple — indeed, even the name has disappeared from the surface of the Greek continent.... Not the slightest drop of undiluted Hellenic blood flows in the veins of the Christian population of present-day Greece.”

Fallmerayer’s theories were attacked by his contemporaries, and he was removed from his post at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. But he remained very influential in European courts, and educated Nazi officers would later use his theories on the Greeks to justify murdering them in the thousands during the occupation in WWII.

Not that it matters, but in case you’re wondering, Modern Greeks are not some subrace of Slav10.

So what does this all have to do with modern Greeks being excluded from telling their own myths? Let’s jump a bit forward, to the 19th century. England inherits half the world in Empire, and becomes the cultural hegemony. As styles and tastes evolved, Neoclassicists began borrowing from their own work, or Renaissance styles, and scarcely involved any actual Ancient models (and even if they did, the paint was worn off on purpose).

From the Age of Enlightenment to World War II, the wealthy and elite were taught Greek and Latin stories that were filtered and translated by English scholars and tutors, who themselves were taught by English tutors. On and on this cycle had gone, for over a hundred years by that point. It had become part of the identity of the elite. A new oral tradition, for the elite to set themselves apart from the less educated, the unenlightened.

Rather than preserving, they would pick and choose the morals and stories that suited their own values, that helped them push their own social agenda. Neoclassicism was everywhere. If you’re wondering why every town hall looks the same, it’s because of Neoclassicism.

Meanwhile, Greece was struggling under occupation. Even when the country fought and gained independence in 1821, it was never seen as equal to the European Powers and the US. Better it be seen as a lost state, a failed state, and Ancient Greece a lost culture. How could the glorious ancients be brought so low? Westerners would rather think of it like Atlantis: something that sprung up with brilliant ideas, something that was lost until the English gloriously rediscovered it. A favorite pastime of the English.

But it’s been many years since the British Empire was dissolved; a century since Neoclassicism was in vogue. Greece is now part of the EU, and it’s a (relatively) stable nation11. Why don’t we see more Greek authors? Well, leaving aside the fact that Winckelmann’s work The History of Art in Antiquity is still lauded as a complete, thorough, and comprehensive description of ancient art, despite its many, many flaws, Neoclassicism left its indelible mark on Western consciousness.

To many, we don’t need stories from actual Greek people; Greek myth is part of the fabric of the Western world, in their opinion.

It’s not like there aren’t talented Greek authors out there writing about Greek myth. We are only left to assume that publishing at large ignores us, because white authors have filled the role quite nicely of a packaged, sanitized, white-washed version that Western audiences expect.12 It is not within us to compromise our culture for the sake of mass appeal. Much of our actual folklore is seen as strange; irrelevant to the “actual” myths, despite the popular conception of those myths being built on copies of copies of copies, like a 2000-year-long game of Telephone.

That’s how you get a Tordotcom anthology of inclusive Greek myth retellings that don’t include a single Greek author on the table of contents.

Recently, Pan Macmillan touted “The best retellings of Greek myths,” without a single Greek author on the list (https://www.panmacmillan.com/blogs/literary/best-books-based-on-mythology).

We’re not diverse enough, is what they’re saying. Our stories aren’t diverse enough.

From a recent interview with Madeline Miller, the author of Circe and The Song of Achilles, there’s a very telling moment when John Plotz, one of the interviewers, says:

“Can I ask why you cherish [the Iliad and the Odyssey]? I mean, given the things that you’ve revealed about them, like the bottom-heaviness of them, why not just toss them out?”

Miller doesn’t disagree, doesn’t push back on the premise of the question. In fact, she goes one further: “I guess I would say that I do want it to be a corrective—in that I want it to be out there as another strong version of the story.”

https://www.publicbooks.org/madeline-miller-on-circe-mythological-realism-and-literary-correctives/ is the full interview if you’re wanting to read it, in case you think my quote is out of context.

She is literally saying here—as a classicist whose understanding of Greek myth is filtered through 2000 years of removal from the actual people they feature—that the original is problematic, and a correction of the record is needed.

A correction of the Odyssey, which features Nausicaa, who bites her tongue and steps up courageously to defend her homeland from a naked, crazed man, and then when Athene summons blinding mist to obscure Odysseus’s form, she guides a donkey bravely through that mist up a mountain to her parent’s palace.

The Odyssey, which features an angry, faithful wife in Penelope who maneuvers her suitors into competing for her hand with an archery competition, knowing that Athene would not guide her wrong.

The Iliad, which shows Greek soldiers sharing their tents with Ares for glory in battle, and mentions it offhandedly, because it was the expected thing.

Miller is capable of reading the originals, yes, but her interpretation is filtered through a modern, Western lens.

Look, I don’t hate Madeline Miller, but she’s upheld as an authority on the subject, while actual Greeks are ignored.

How are we to fight against this?

It’s hard not to be pessimistic about things. But I’m encouraged by the reaction to the Tordotcom thread, where many people were quote tweeting and in the replies commenting about the hypocrisy.

Maybe things can be shifted. My hope is that one day, just as the promise is for every other marginalized community, that Greek people can tell their own stories.

And as for Greeks: to be Greek is to be part of a culture on the verge of extinction. We’ll do what we have since the Fourth Crusade. We’ll survive, and tell our stories to any that will listen.

If you’re interested, I’ve assembled a list of Greek authors writing and retelling Greek myth below.

Eugenia Triantafyllou’s short, My Country is a Ghost, is a tear-jerking story that any immigrant will appreciate. It also features daimons, ancestral spirits that almost no one outside of Greece knows about. Bonesoup is also a favorite of mine.

Danai Christopoulou’s Bride of the Gulf is an urgent, timely yet old-world feeling story about loss and regret. And killer mermaids.

Natalia Theodoridou’s Ribbons is incredible.

Zoi Athanassiadou’s Aegean Fish Pie is a recent favorite of mine. I need more from them.

Antony Paschos’ Pinebark I need to finish reading but it’s special. It truly is.

I’ve also tried my hand at retelling the story of Adrasteia, one of Zeus’ wet nurses, who hid him from his murderous father Kronos. You can read that here:

He would write about goddesses and mythological heroines pining for their lovers (really PINING).

It was fashionable back then to throw in a mention or two of that.

The Slavs, Avars, Bulgars, Pannonians, Khazarians; so so so many incursions.

Mind you there might’ve been one church for about three seconds in 10 AD, since there was the Coptic pope and the Syriac pope and the Nestorian pope etc.

Gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss.

The HRE is a historiographical naming to separate the two entities—Charlemagne was only ever called Emperor of the Romans by his contemporaries.

Over bread of all things, look it up.

At least in the form it took in history—Hellenistic revival was happening but not nearly to the same extent, and mostly came from Greek mercenaries from the East and their families coming to Italy for work.

Disentangling the original folklore is difficult, because there are so many different versions among different parts of Greece. But it would be easier if Westerners stopped making up new versions.

Although arguably, economic oppression from the EU is a new kind of colonialism.

Jennifer Saint has made lots of money pretending that her versions of the myths are true.

I don't think most people nowadays know what to make of modern day Greeks. They're sort of like Mayans or Egyptians: an ancient civilization seen as entirely separate from the people who live there now.